PHOENIX’S FIRST MARSHAL’S OFFICE & JAIL

Lawless became so bad that a mass meeting was held in Phoenix on April 3, 1872, to “devise the best means of safety from lawless Sonorans and others.” A volunteer company of men was appointed on a safety committee “to inquire into the character of strangers and to notify the evil disposed to leave.” On April 10, 1874, the president issued a patent for the present site of Phoenix. After Phoenix was incorporated as a city on February 25, 1881, it also formed its own law enforcement. In 1881, Henry Garfias was elected by 2,500 residents as the first city marshal in the first elections of the newly incorporated city. For six years, he served as the primary law enforcement office. Marshal Garfias was an influential community member which most likely helped him get elected as the first Phoenix town marshal. Marshal Garfias’ staff consisted of his jailer, H.C. McDonald.

arizona rangers

Arizona’s reputation as the West’s last refuge for hard-bitten desperados was a major reason its admittance to statehood was delayed so long. The proximity to the Mexican border, bad roads, poor communication, and rugged terrain made pursuit and capture of outlaws almost impossible.

To make matters worse, rural residents were sometimes hesitant to assist peace officers because many of their neighbors were outlaws, and they didn’t want to incur vengeance. The hard men who rode the Arizona Territory were products of a lawless, and violent post-Civil War era characterized by range wars and feuds.

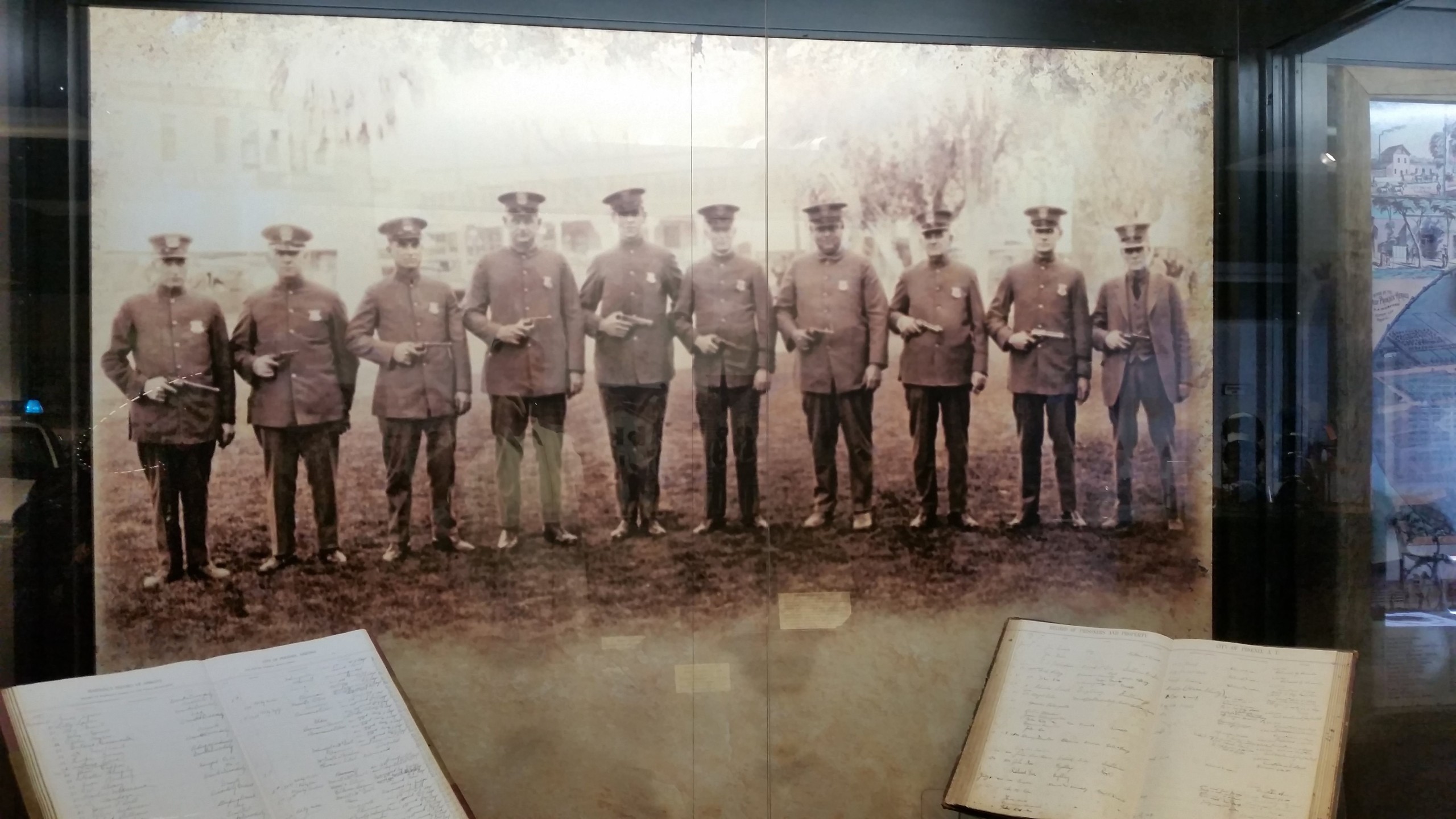

EARLY LAW ENFORCEMENT

Phoenix rises from the desert with the small-town site. In the beginning, the town of Phoenix had marshals until the form of government changed. We went from looking like cowboys to actual uniformed officers with dress jackets, badges, and hats. The city was relatively small when compared to today with more than 1.5 million residents and 550 square mile of area which is geographically larger than Los Angeles, California. The city was only a few square miles with farm fields surrounding the original town site surrounded by canal originally dug by the Hohokam Indians.

1900-1920 LAW ENFORCEMENT

In 1929, patrolmen worked six days a week and were paid $100 a month. The police department moved into the west section of the new city-county building at 17 South 2nd Avenue. The building included jail cells on the top two floors. The museum is located in what was the Phoenix Police Department from 1928 until 1974.

TIN LIZZIE

The Phoenix Police Department had convertible top police cars. One of the first cars to catch speeders doing 15 MPH in a 12 MPH was our 1919 Ford. In the early 1900’s, car dealers would try to create publicity for their new automobiles by hosting car races. In 1922, a championship race was held in Pikes Peak, Colorado. Entered as one of the contestants was Noel Bullock and his Model T, named “Old Liz.”

POLICE WORK AFTER WWII

Many changes to police work occurred after World War II, from uniforms to weapons. The department began to become more standardized in its academy, training and policies. In 1933 the department started its first radio broadcast.

BE SWORN IN AS A POLICE OFFICER DURING YOUR VISIT

Children of all ages can try on a real Phoenix Police uniform shirt while visiting the museum. Don’t forget to get your coloring book, crayons and your own sticker badge before you leave!

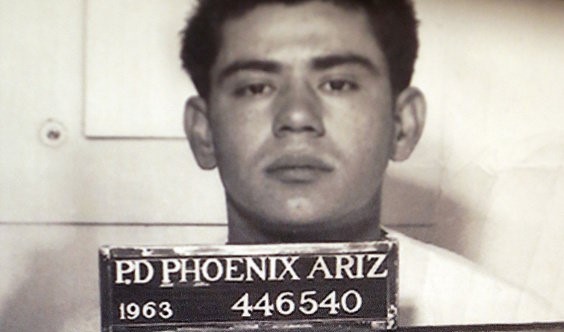

PHOENIX’S CONNECTION TO MIRANDA WARNINGS “YOU HAVE THE RIGHT TO REMAIN SILENT!”

In the late evening hours of March 3, 1963, a young Phoenix woman was kidnapped, sexually assaulted and robbed while walking from a bus stop. Ten days later, on March 13, 1963, Ernesto Miranda was arrested by the Phoenix Police for the assault. This set in motion a series of court hearings which resulted in a U.S. Supreme Court decision that would impact interviews between law enforcement and those suspected of crimes.

POLICE HELICOPTERS, CARS AND MOTORCYCLES

Inside the museum you will see a 1919 Model T police car, police motorcycles, bomb robots, and even a full-size helicopter. In 1974, the Air patrol unit was established initially consisting of one helicopter. A few months later, a fixed wing aircraft and two additional helicopters were added.

We even have a fully size police car to take photos in!

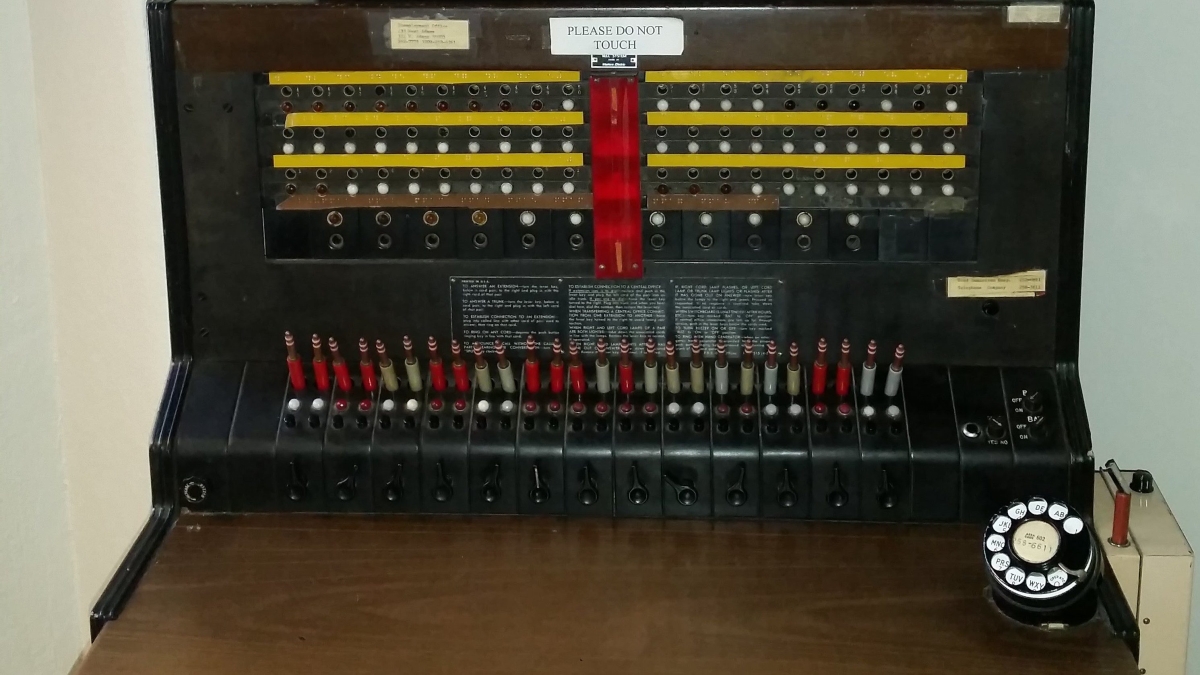

CALLING ALL CARS

Early switchboard to take calls.

PATCHES AND BADGES

Check out our display of uniform patches from around the world. See if you can find your city or town in our collection. We also have an exhibit of the progression of our Police Departments patches and badges over the years.

SWAT

An exciting exhibit on the Special Assignments Unit (SWAT) is a must for all visitors to see. See why they are such a well-trained unit ready to take on threats to the public.

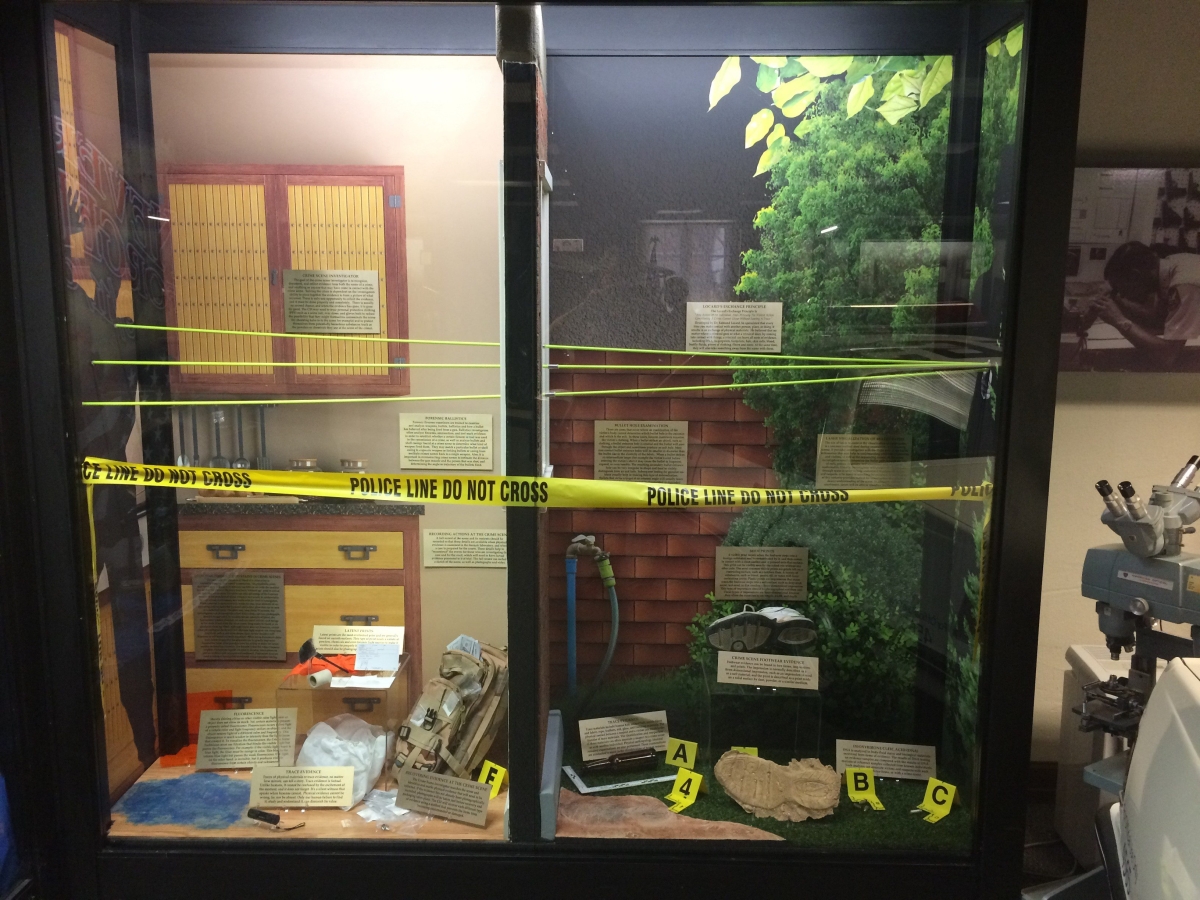

C.S.I. (CRIME SCENE INVESTIGATIONS)

Our Crime Scene Investigation exhibit allows visitors to view a sample crime scene (suitable for children) to learn about the various methods for gathering evidence and investigating a crime scene. See if you can discover the clues and solve the crime.